Animals have long been a major theme of children's books. Animal studies critics historicize the beginning of this phenomenon, bemoaning the resulting infantilization of animals. When children and animals become so closely associated, at least in the Western imagination, they are both demeaned, according to these critics, at least: animals become like children, and children like animals.

Having observed my own two children fall in love with reading, books, and their imaginations, not to mention animals, through children's books, it's hard for me to resist a great children's book about animals. But I'm particularly moved when I find a book that does justice to both animals and children. They All Saw a Cat, by Brendan Wenzel, is one such book.

Got Umwelt?

The whole premise of this very simply written book is that all kinds of animals perceive the cat in all kinds of different ways. The illustrations are evocative of a diversity of umwelts, or worldviews, to use Jakob von Uexküll's term. Each page shows a different animal perceiving the cat, and each illustration evokes the unique possible ways that those different animals may perceive the cat.

So, for example, the worm might only perceive the cat through vibrations it feels underground as the cat walks above. The illustration of this page shows only lines underground in the shape of a cat, surrounding the worm.

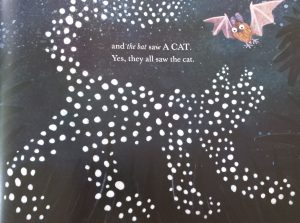

The bee sees a bunch of colored dots that make up a cat face. The fox mostly hears a cat, right? So it "sees"* in the illustration, at least, mostly a bell hanging around the cat's neck. How about a bat? It "sees" the cat as echolocation, of course. How would you represent that in a visual illustration? In the book, it's a bunch of dots in the night that make the shape of a cat. We "see" (or feel, or hear, or sense) the cat from the perspective of a snake (represented by the illustrator in infrared), a child, a bird, a bee, a flea, etc.

|

| How would a bat "see" a cat? |

From the perspective of animal studies, this is precisely the kind of appreciation of animals we need more of in the world. The reason for this is because animal studies critics don't like the fact that most Western representations of animals project human qualities or desires onto animals instead of seeing animals as potentially carrying their own perspectives, desires, and intelligences. In most children's books, this means that animals play supportive, secondary roles to the child or human in the story. They are blank slates on which to play out the drama of human needs.

They All Saw a Cat totally rejects that Western trope of the animal in children's books. It asks readers to imagine perceiving the world through all our senses, like so many animals do. It demands that readers imagine what it would be like to go through the world as a bat, or a snake, or a bee, or even a worm. In other words, it simultaneously asks readers to transcend our hubristic humanism that universalizes experience and knowledge of the world, and to put themselves in the place of each of these animals. Through the worm, we learn what it might feel like to be anybody but ourselves. This is the most important foundation of empathy. Surely, if we're going to exploit animals in children's stories, this would be the right reason.

|

| How would a fish "see" a cat? Watery and huge, looking at it through the fishbowl glass! |

Of course, our protagonist is the cat, who walks through each page, encountering each of these animals. After meeting a few animals, the cat gets its own page again, anchoring the reader in its perspective. Every few pages, we read again, "And the cat walked through the world, with its whiskers, ears, and paws."

Why does Wenzel reiterate how the cat walked through the world, "with its whiskers, ears, and paws"? What is it about these things-- whiskers, ears, and paws, that require repetition in such a word-shy book? What do whiskers, ears, and paws do for the cat? Why are they so important? Once again, they are the cat's main sensing organs-- notice that "eyes" are not part of that list. Wenzel wants us to de-privilege sight/vision, which is humans' (or at least, Western humans') primary way of knowing the world. Think about how "we" (i.e. me and lots of people like me, but not necessarily you), come to know what is "true" in the world-- through SIGHT. "You have to see it to believe it," right?

I can't help but think that Wenzel's totally down with von Uexküll, and really wants us to think about how other senses might tap into other truths, other worlds. This is a crucial insight of the philosophical theory of phenomenology--that the body (i.e. senses), not the mind (i.e. reason) gets us to the truth. So, the body and all its senses, no matter what kind of animal you are, determines your truth. This is radical. It rejects the predominant theory of the father of Western philosophy, Rene Descartes, who told us that "cogito ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am). Many cite Cartesian dualism for separating humans from nature, and for authorizing the exploitation of all nature, including animals, as resources to be used for human needs. In other words, if human reason derived through vision is the basis of all truth and knowledge, then animals (and anybody else) who perceives the world in any other way is less than human.

Wenzel is rocking my world with this children's book, which privileges all kinds of ways of perceiving multiple realities. The book challenges any one objective, universal (e.g. "human") way of knowing truth, and privileges the truth that emerges from individual uniqueness-- what feminist philosophers call "standpoints". How does Wenzel pack all this heady stuff into a children's book?

The book asks readers to get outside of themselves (and the realities we're imposing upon them) to grasp the ways in which other creatures and people feel and understand the world differently than they do.

The potential here for a nicer world, dare I say social justice, is huge. But what I love about the book is that Wenzel makes this argument without costing animals their own agency, or rendering their lives secondary to human plots and desires.

|

| My daughter came up with the idea to paint how the bee sees the cat. See, this book ROCKS! |

*Why does Wenzel use the verb "sees" for all the animals, when his whole point is to get us out of ocularcentrism? I think it's to ask readers to rethink what "see" might mean for other creatures. Of course, you can't "see" vibrations or sounds, but that's the genius of the book: how to represent vibrations, sounds, heat, fear, and non-normative sight (e.g. "bird's eye view") in illustration? Even though he uses "sees" when he really means "feels" or "hears", the accompanying illustrations expose the limits of the visual.